First Ride: Auckland Cycle Works Marra Prototype with KOLARP Suspension

The Auckland Cycle Works Marra is a dual short-link enduro bike created by bike shop owner, Gary Ewing. The unusual linkage layout arises from an atypical, back-to-basics approach to bike design; rather than making use of any computer aided design, Gary chooses instead to crack out the Lego to visualize and model linkage layouts. That can be an incredibly useful exercise, at least in gaining some level of understanding as to how different linkages deliver different axle paths; Gary's video of this process is worth a view, if only to grasp just how aggressive the rearward axle path of his KOLARP suspension design is.

However, it's worth pointing out that, at least to my knowledge, no other modern day suspension bike on the market has been designed in this way, i.e. without the use of a computer and the precision that comes with conventional suspension analysis tools.

However, it's worth pointing out that, at least to my knowledge, no other modern day suspension bike on the market has been designed in this way, i.e. without the use of a computer and the precision that comes with conventional suspension analysis tools.

Marra V2 Details

• Steel frame

• 165mm travel, 180mm fork

• Mixed wheels

• Size tested: 451mm reach

• Weight: 38 lb / 17.28 kg (w/o pedals)

• Head angle: 64°

• Seat tube angle: 76°

• BB height (unsagged): 350mm

• Rear-center length (unsagged): 416mm

• Rear-center length (sagged): 441.5mm

• Rear-center length at bottom-out: 476mm

• Price: £5,500 (frame only, with custom geometry)

• More info: aucklandcycle.works

• Steel frame

• 165mm travel, 180mm fork

• Mixed wheels

• Size tested: 451mm reach

• Weight: 38 lb / 17.28 kg (w/o pedals)

• Head angle: 64°

• Seat tube angle: 76°

• BB height (unsagged): 350mm

• Rear-center length (unsagged): 416mm

• Rear-center length (sagged): 441.5mm

• Rear-center length at bottom-out: 476mm

• Price: £5,500 (frame only, with custom geometry)

• More info: aucklandcycle.works

Outcomes of Gary's design process were on display at Bespoked in Dresden; the Marra and the Reiver are nothing if not head turners. Both run versions of the Kind of Like a Rearward Pivot URT design, though the Reiver is slightly more out there, given that it houses the BB on a moving link.

The Marra is now available to pre-order for the lofty price of £5,500 for the frame. Tested here is the V2 prototype. Testing of prototypes isn't something we make a habit of, but it's nice to make an exception every once in a while. Also, having followed Gary's development story over the last few years, and upon learning that he doesn't know how he could possibly make the KOLARP suspension design any better than it already is, the temptation to give it a shot was all too much.

Frame Details & Suspension Design

The Marra V2 prototype is constructed from steel tubing, welded to Gary's specifications by Coal Bikes owner, Gavin White. Its suspension takes the form of a short link four-bar layout, with an idler pulley mounted directly to the lower link, such that its position relative to the chainring moves as the rear wheel is displaced. This does indeed fall under the scope of the I-Track patent.

Through compression, the lower link rotates counter-clockwise for most of the travel, until it stops at 147mm and begins to rotate clockwise until bottom-out. The upper link rotates counter-clockwise throughout compression, driving the shock via an extender, which is unusually long in the context of the 65mm stroke shock that it's mounted to. The resulting axle path is aggressively rearward; unsagged, the rear-center is 416mm (as tested), extending to 441.5mm at sag, and 476mm at bottom-out.

It's not 100% rearward; the inflection point comes at around 113mm travel, at which point the rear axle has moved rearwards along the horizontal by a substantial 32mm from the unloaded state - that's a bigger increase than we see on some of the highest single pivot enduro bikes, like the Forbidden Dreadnought, but not quite as much as the 45mm rearward movement exhibited by the wild-looking Aper KOMPace.

There are two points of adjustment on this frame. Firstly, the rear-center length can be adjusted through 30mm, in 5mm increments, by virtue of the sliding dropout - Gary's unique version of which is T-Type compatible. That's a pretty generous range of adjustment. Lengthening the stay does of course increase the axle's leverage over the shock. Going from the shortest position to the longest position, the increase in leverage is enough to warrant around an 18 psi increase in shock pressure to achieve equivalent sag.

Then, there's the forward shock mount. Though Gary's original intention was to have use of a full range of adjustment here, in practice, only a few of the furthermost forward positions are viable, owing to the startlingly high leverage ratios that the rearward positions give. More on that shortly.

Ride Impressions

I rode the the Marra in the 416mm chainstay position, with a 230mm x 65mm Cane Creek Kitsuma air shock mounted in the furthermost forward position, and a 180mm travel Fox 38 fork. That gives the bike its lowest possible bottom bracket height of around 350mm, which is pretty high in the grand scheme. Positioning it further back raises the BB, lengthens the reach, shortens the rear-center, and steepens the head and seat tube angles.

Gary's recommendation was to run sag between 20% and 25%, with both high- and low-speed compression and rebound damping close to fully open. Weighing just 59 kg, that's how I would normally run the dials of any shock, to get it as active as possible at the relatively low pressures I would normally run. That said, that sag range is very much on the firm end of the spectrum, especially with such a long travel bike. For context, a conventional enduro bike would normally run around 30% sag, while a reduced sag of 20-25% is normally reserved for much shorter travel bikes, such as 100-120mm travel XC race bikes.

Gary's recommendation was to run sag between 20% and 25%, with both high- and low-speed compression and rebound damping close to fully open. Weighing just 59 kg, that's how I would normally run the dials of any shock, to get it as active as possible at the relatively low pressures I would normally run. That said, that sag range is very much on the firm end of the spectrum, especially with such a long travel bike. For context, a conventional enduro bike would normally run around 30% sag, while a reduced sag of 20-25% is normally reserved for much shorter travel bikes, such as 100-120mm travel XC race bikes.

Hopping onto the Marra, the first thing I noticed was how tall the bike is. Relatively little sag combined with 155mm cranks from Hope, and the increased saddle height they require, gave me a center of gravity that felt substantially higher than I am accustomed to. I felt perched atop the bike, which took some getting used to, though the seat tube angle felt plenty steep enough to give an upright climbing position, with the BB tucked underneath my hips in a comfortable position.

On the whole, the bike felt very inefficient on fire road climbs. I didn't feel as though the suspension was to blame here, owing to it feeling impressively neutral under pedaling; there really was little to no pedal-induced bob to speak of, even with the shock's damper settings fully open. I'm more tempted to apportion blame to the bike's 17.3 kg (38.1 lb) heft, and the extra drivetrain drag introduced by two extra pulleys; the tensioner pulley and the idler. I didn't do a great deal of technical climbing, but on the odd occasion I did, the rear end felt quite muted over bumps, and traction was not lacking.

The bike has a reach of 451mm. That is approaching (but not exceeding) the upper end of the range that I'd choose to ride, but with a 35mm stem it was well within the realm of manageable. I was able to maneuver the bike around to hit my usual lines on well-known enduro trails without undue aggression.

What I wasn't able to do was hit those lines with any of the usual pace I'm accustomed to. On the mellower gradient trails, littered with small gaps over furrows and root clusters, I found I was failing to make the backside of features that are normally very achievable. The bike felt sluggish through these twisty, busy sections of track, and was not able to carry good speed. The rear end felt harsh, as though it wasn't efficiently absorbing bumps, delivering a distinct lack of composure. Figuring out where to position my weight between the two wheels proved difficult, and it often felt as though I was getting rocked back and forth, never quite getting a good, consistent body position where the bike felt predictable. There were a few glimpses of things starting to work, but they were few and far between.

I did, by and large, stick to Gary's recommendations of around 23% sag. Curiosity did get the better of me, however, and I did do one run with a more standard 30% sag just to see how that felt; sadly, it did not improve matters, and the bike simply felt as though it was folding in compressive corners, with marked tendency to understeer.

To get some consistent runs, I completed seven shuttle-assisted laps of a well-established downhill race track. After a couple of sighting laps, I incrementally adjusted sag from around 25% down to 20%. With more air in the shock, the bike actually felt more supple off the top, with a less raw feel to it over the smaller bumps in the track. Still, it felt harsh on successive hits, jarring almost, and that feeling of the rear wheel getting easily hung up did not go away.

That said, there was no discernible pedal kickback to speak of, even under firm braking through rough terrain. The harshness instead felt to be coming up through the bike, as though the rear wheel wasn't able to get up and out of the way over bumps, particularly while on the brakes over braking bumps. Throughout the day, I developed an enhanced appreciation for the benefits of not braking in corners - a rule of basic riding technique that can help one carry more speed through corners. This is of course something I've been familiar with for many years, but the benefits of rigidly applying that rule felt particularly important while riding the Marra, if only to make it more predictable through corners.

In higher speed, well-supported corners where I could stay off the brakes, the Marra felt at its most predictable. The geometry felt well preserved throughout the apex of the turns, and it was easy enough to hold a consistent line on berms. As the number of laps increased, and the sag reduced, the riding experience improved as I subconsciously adapted to how the bike behaves.

Dan Roberts (of Behind the Numbers fame), did a spot of suspension analysis on this one to help put some numbers to what's going on here. To be perfectly clear, I refrained from looking at any kinematic graphs until I had ridden the Marra on several occasions. The above account was written up in advance of seeing the outcome of the suspension analysis.

Kinematic

The graphs are illuminating, to say the least. The leverage curve goes some way to explaining the harshness of the Marra's ride quality. The leverage, or the mechanical advantage that the rear axle has over the shock, is incredibly high initially at 3.8. That is something that can and does give a very supple feel on touch down. However, that leverage ratio falls incredibly sharply, with more leverage ratio change in the first 90mm of travel than other bikes have over their whole travel range. Within 90mm travel, the ratio has already dropped to its lowest value of around 2.34, and from thereon becomes regressive to bottom-out.

With the Marra's leverage curve being so progressive through that initial portion, the suspension actually uses quite a lot of its rear wheel travel relative to sag at the shock. A sag of 20% at the shock gives a rear wheel travel sag of 39.5mm (24% sag), meaning the bike has less positive travel available to use as compared to bikes that see less progression through the early stroke.

The Cane Creek Kitsuma on the Marra has a stock off-the-shelf tune, not custom to the kinematic of the Marra. In terms of tuning suspension for such a leverage curve... well, manufacturers don't tend to work with such high starting ratios. As an example, RockShox recommend that rear suspension designs have an average leverage ratio that sits between 3.0 and 2.1, and the Marra does conform to that with an average leverage ratio of 2.54. The difficulty comes with the huge variation in leverage ratio throughout the travel; tuning a shock to offer effective damping over such a range is, I am reliably informed, not terribly viable, and a tuner would effectively have to make a decision on which portion of the travel to tune the damper for, leading to big compromises either way.

While I felt as though much of the bike's unpredictable ride feel could be attributed to the dramatic changes in rear-center length, the high leverage ratios throughout the first portion of the bike's travel could also have been a contributory factor. High leverage ratios deliver a relatively slow shaft speed, with little damping force generated as a result, something that may have resulted in faster rebound speeds than desired. That'd be compounded by the fact that a high leverage ratio requires relatively more shock pressure to achieve the same level of sag (131 psi gave 23% sag).

The Marra's dramatic drop in leverage ratio is occurring while the rear-center length is increasing significantly. At the point at which the rear axle stops tracking rearwards, the rear-center length has grown by a whopping 48mm from the unloaded state, which is around twice as much growth that a conventional bike sees throughout its entire travel.

Meaningful changes, both to how much support is offered up by the rear suspension, and how long the rear-center length is, are occurring at a portion in the travel that the bike spends most of its time oscillating about. This unusual set of characteristics is likely responsible for the lack of predictability I experienced while riding the Marra.

There is minimal cross-talk between chain forces and suspension movement while riding in the smaller sprockets of the cassette, as one does while descending. The positioning of the idler pulley on the moving lower link, as per the i-track patent, keeps chain growth to a minimum in these gears. In fact, in the 10T sprocket, pedal kickback values drop into negative values, meaning the required length of chain between the cassette, idler pulley and chainring actually decreases. In the absence of a chain guide, such a design would likely have a tendency to cause the chain to come away from the teeth of the idler or the chainring thanks to the addition of unnecessary chain links along those top spans of chain.

Meanwhile, for the larger cogs of the cassette, pedal kickback is much greater. In the 52T, the pedal kickback value sits at 7° at sag, doubling to 14° at just over half way into the travel. It's worth pointing out here that this is higher than we see for other idler-equipped enduro bikes, and actually comparable to more conventional Horst pivot designs. All that said, I honestly can't say I was able to discern that while riding. If anything, I'd say the pedaling action felt pretty smooth over rougher ground, and traction wasn't an issue. To be fair, more noticeable than anything was the change in cadence that comes with very short (155mm) cranks. This was distracting enough that it was difficult to notice much else about the pedaling feel.

As you might expect, anti-squat is at its highest in the climbing gears. Though it is remarkably high at 179% (for 32-52T) in an unloaded state, it drops sharply to 102% for 23% sag. That's a value that many manufacturers aim for, as it delivers a bike that doesn't sink into its suspension travel under pedal-induced accelerations. This is the silver-lining of the Marra's suspension design.

However, those desirable anti-squat values are only present through a small window around sag, and only really apply to the easiest gears. The story is quite different when moving to the smaller cogs of the cassette. In fact, the anti-squat drops into negative values in the 10T cog. In the real world, that meant the bike wallowed while sprinting in harder gears, making it feel mushy and inefficient. No suspension design is immune to variation in anti-squat through different gears of the cassette, but the Marra's KOLARP suspension design brings about a much wider variation than most.

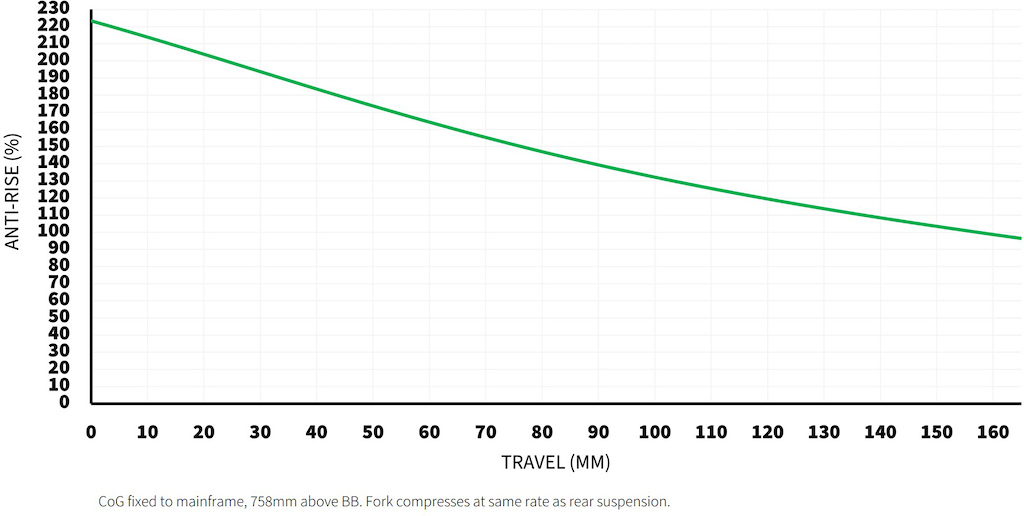

A major contributor to the harsh ride feel of the Marra is how the suspension behaves under braking. Anti-rise is the metric we use to describe suspension's tendency to either rise (extend) or compress (squat) under braking. Many designers look to keep anti-rise around about or south of 100%, which theoretically would give a suspension platform that remains neutral, or even extends a little, under braking. It essentially aims to keep the suspension active under braking, so that the rear wheel can continue to move up and out of the way of consecutive bumps on the trail.

The anti-rise of the Marra is inordinately high, sitting at 179% at around 23% sag. Later on in the travel, anti-rise will only drop as low as 97%, which is higher than many bikes will start at. In real life, that translates to the suspension being forced into compression under braking, pushing the bike to a much lower leverage ratio and a higher spring rate, where the suspension is less able to effectively absorb consecutive hits.

Having listened to Gary's thoughts on suspension design, and having read the information on his website about the KOLARP kinematic, these high anti-rise values were very much intentional. His interpretation however, is that the suspension stays at sag under braking.

Parting Thoughts

To some, it may seem as though the many of the mainstream mountain bike brands are are lacking in creativity when it comes to suspension design. Many of the big players are sticking with comparatively plain-looking, conventional designs like the linkage-driven single-pivot or the four-bar Horst link. While these aren't especially visually exciting, they are well-understood designs that can be tweaked subtly to deliver a ride feel that is very predictable, and easy to ride for a wide range of bike handling competencies.

Suspension designers can wade in here and tell me i'm wrong, if they like. But, at least to my mind, we are past the point of reinventing the proverbial wheel when it comes to linkage layouts. There are so many tried and tested designs out there that do an excellent job of providing good support, while balancing pedaling efficiency and maintaining a good, safe-feeling geometry under braking.

That's not to say that there aren't some innovative new suspension designs on the horizon. Specialized and Norco spring to mind, here. Even they aren't reinventing the wheel, however. Both platforms (still not commercially available) are about finding ways to independently adjust kinematic parameters (anti-rise, axle path, leverage curve), with a view to fine-tuning these elements to suit different terrain types (or more specifically, World Cup race tracks).

I guess what I'm trying to say here, is that I'm not surprised that some of Gary's claims around how the KOLARP suspension design works haven't materialized in the Marra. The Auckland Cycle Works website reads, "KOLARP is a new patented suspension system that delivers better performance uphill, downhill, pedaling and braking." It would be surprising if anyone with a fraction of the budget of these companies could, without the use of modern computer aided design and suspension analysis tools, design a bike that out-performed incumbent, race-winning designs.

Sadly, the Auckland Cycle Works Marra prototype has not hit the mark. In reality, many of its suspension characteristics are not desirable, which is why you'll struggle to find a modern day bike with a kinematic that comes close to that of the Marra.

The Production Marra

The Marra V2 tested here is just a prototype, after all. We reached out to Gary to find out what changes the production Marra will be subject to. His response was as follows:

"The prototype bike that you rode had an issue which required swapping out rear shocks, this ended up raising the BB height by 10mm and putting the bike outside the window where the various kinematic forces are balanced. This would also prevent you pushing the bike through corners with your feet. Since the front centre shortens and the rear centre lengthens by very similar amounts, standing centrally in the bike is a technique which helps Marra perform at its best. I offered to remedy the adjustment range by fitting a shorter shock yoke.

My own further testing with the shorter yoke highlighted the importance of this adjustment and puts the shock back into the centre of the range of adjustment. The rider has the opportunity to fine-tune the BB height to their exact preference.

I’m aware that all my kinematic values are outliers, but there is a balance to be found between the highly curved axle path and the equally curved leverage curve. The raised BB means that this balance was missed during these test rides.

The next iterations of Marra and Reiver has a number of changes, maintaining adjustability and reducing weight. R&D is ongoing in both CAD and Lego!"

Pricing & Availability

In 2024, Auckland Cycle Works will produce only 25 Marra frames. Pre-order is open now, with a 50% down payment of £2,750 required to secure a spot. In that £5,500 total price, Gary is offering custom geometry, the choice of any color imaginable, and those hyper-adjustable dropouts.

Author Info:

Must Read This Week

www.youtube.com/watch?v=_vmAksFRydU&t=345s&ab_channel=motocrossactionmagazine

Kind of makes me wonder if someone should build similar suspension on a MTB but with less than 300mm of travel.

I'm considering going down the same route (custom frame) but with a mid or mid high pivot. Still wondering if I will add linkage or not.

Also you can't really say "well it would've been perfect had I just given you a slightly shorter shock which I didn't" as an excuse.

It is always good to test new things and I think it is great to get the info out. There might be some changes that will make the concept fulfill a niche, but it isn't there yet, it would seem.

If you want a killer steel FS handmade whip and don’t wanna go broke, Ferrum is the way to go.

‘Hold my multiple idler jockeys’

Even if the pricing is in NZD and not £, 5500 NZD for a frame is mental.

You shouldn’t need to be one a dentist to buy a bike frame let alone spending more on components.

Thank you but no, cool frame though

Umm, not according to those charts. The 10t lines show both kickback and large squat interactions.

Negative pedal-kickback is still interaction, and means it will kickback when extending instead of compressing, which is going to feel weird. Contributes to the _massive_ PRO-squat: aproaching negative-two-hundred percent anti-squat (double negative FTW!) at mid-travel, what?! Pedal hard out of a compression and you're actively pulling the suspension into travel significantly more than the weight transfer alone. Traction is not going to be plentiful.

And that anti-rise curve certainly explains your feelings re: braking bumps. Both braking and pedaling (in descending gears) just want to pull the suspension down ever further. Weird.

This feels like a great way to teach design in a very interactive way. I came away impressed by just how many different approaches are out there.

After - “the bike is outside the window where the various kinematic forces are balanced”.

1. you like chainslap and being in the wrong gear

2. removing your rear wheel during service

3. you ride a BMX bike with 28/10 gearing

So this very expensive custom frame got panned, and the names of a couple o’ big n b its are dropped, nice

Suspension is for descending.

Drivetrain drag can be reduced by a smaller chainring and cassette, as can weight.

Interesting read here.

nsmb.com/articles/high-pivot-gearing-hyjinks

Again, all terrain dependent, but many people I ride with are on 28t's and wouldn't consider going back.

can't take anything serious from someone that writes that.